My mother died on a cool Monday night in October. It was no surprise, just the last moment in a slow surrender of her body to its 92 years and encroaching dementia. Having noticed the subtle signs of a body changing its earthly direction, the director at the nursing home called my father that morning, and he and my siblings kept vigil with her all day. But in the conceited fumbling the living do to calculate or control the dying, everyone figured she would linger through the night. And so, the nurses counseled Dad to go to the lounge for a nap, assuring him they would alert him if it seemed she decided to go.

My mother died on a cool Monday night in October. It was no surprise, just the last moment in a slow surrender of her body to its 92 years and encroaching dementia. Having noticed the subtle signs of a body changing its earthly direction, the director at the nursing home called my father that morning, and he and my siblings kept vigil with her all day. But in the conceited fumbling the living do to calculate or control the dying, everyone figured she would linger through the night. And so, the nurses counseled Dad to go to the lounge for a nap, assuring him they would alert him if it seemed she decided to go.

Which she did – about 5 minutes after he settled into his lounge chair.

I don’t know why she chose to leave us on that day as there was nothing special about it. No anniversary or birthday, not even the end of a long week, when a person might be glad to lie down and sleep for awhile. Maybe it was her intention to slip away like that. An average day, another soul passing.

Regardless of the reason, Mom’s passing set in motion the plan she had laid out for the last ceremony she would attend, her funeral.

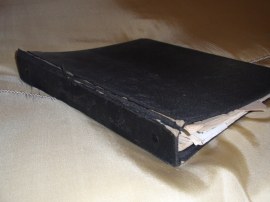

Like any good party planner – and she was a good party planner – Mom had locked down all the details of her final event, what she would wear, who among her children would do the readings, sing the songs, and, no, the wake was not to be held at the family home. She didn’t want all those people traipsing through the house she had furnished with such care over 50 years. She even specified that she be buried with her first-communion rosary and prayer book. At some point, while she worked out her plans during her decreasing moments of lucidity, my siblings and I joked that we would pack a flask of her favorite cocktail – a Manhattan – into her casket so she could toast us once she got past the pearly gates.

As part of her plan, she had requested that her six grandsons bear her casket during the funeral. Her wish meant my 15-year-old son would need to be prepared for his role as pallbearer, an idea (and word) entirely new to him. As he’s a reticent child, I took extra care in explaining to him why his grandmother required his assistance at her funeral.

“Well, in a Catholic funeral, see, someone has to carry the casket into and out of the church. And so your grandma wanted you to be one of those people,” I said.

He looked at me, eyes wide, as if he had just been asked to leap untethered from an airplane.

Trying to normalize what to him, I imagined, seemed like a very strange task, I slipped into my teacher role to explain further.

“It’s primarily a symbolic role,” I said. “The funeral director will tell you what to do, and you’ll have your cousins to help. You probably won’t have to carry the casket very far because they put it on a cart to move it around. It’s just in an out of the funeral home and church. There’s not likely to be any real heavy lifting; your grandma weighed only 90 pounds when she died.”

As my son’s entire teenage wardrobe consisted of T-shirts, jeans and sneakers – passable attire for any event in the Pacific Northwest but not in the least bit acceptable for a solemn ceremony in the conservative Midwest – my husband and I patched together suitable clothing for him to wear — my white button-down Oxford shirt, a tie, belt and shoes from my husband’s collection, and a pair of black pants hastily purchased at the local Target store. I called my daughter, who was away at college, and arranged for her to meet us in my hometown for the funeral, a trip best accomplished by bus. Along with arranging the ticket, I instructed her to bring the navy blazer she had borrowed from me for her brother to wear. So, with borrowed clothes packed, the dog stowed at the kennel, and airline tickets in hand, we set off for the heartland.

Though Mom had died just before midnight on that Monday, the funeral was scheduled for the following Saturday to allow long-distance relatives (primarily us) to get there. My daughter arrived in town on the bus on Friday afternoon. The three of us flew in that evening, which meant we missed the traditional calling hours at the funeral home. I didn’t mind, as I couldn’t imagine standing around the funeral home for several hours while friends and relatives filed past the open coffin, talking in low voices about how good Mom looked. Of course she looked good. This was a woman who never missed an appointment with her hairdresser when she was alive (or after she’d died, for that matter. Her favorite hairdresser did one last curl and spray for her final party.)

Although we didn’t get there in time for calling hours, we did arrive in enough time to get dinner before checking into the hotel. My husband, ever the food hound, had already researched local restaurants on his cell phone, and directed us to an Italian restaurant tucked away on a side street in a neighborhood I’d never seen before, though I had lived in the area for 20 years. The restaurant resembled a 1920s speakeasy, with a buzzer to ring at the door to gain admittance and a long wooden bar behind which stood rows of glass bottles filled with varying levels of colored liquid. Along the walls were framed photos of famous people like Frank Sinatra and Ava Gardner, but the overall mafia vibe was broken by the Willie Nelson songs playing loudly over the stereo system.

Hungry as we were, we ordered too much food – an appetizer and huge plates of pasta, along with salad, bread and beverages. While we waited for our order, I sought out the women’s restroom, which was down a flight of stairs lined with stonework. There were even more pictures along the way, the most noticeable of which was a larger-than-life painting of a man on the wall just inside the restroom door. This man, painted to resemble Michelangelo’s David, was nude, except for a fig leaf placed in the customary spot. In the center of the fig leaf was a silver knob, much like you’d find on a cupboard in your kitchen.

There are moments in life when your brain registers what’s coming just slightly behind the motion of your hand. I pulled the knob in the middle of the fig leaf, which lifted a small door to reveal the man’s penis painted in detail on the wall beneath. As if that scenario weren’t mortifying enough, the door was rigged to a siren that blared loud enough to be heard upstairs in the dining room. Jumping swiftly back and dropping the door, I quickly went about my task and returned to the table, trying not to look sheepish.

Between the salad and entrée, my daughter decided she needed to use the restroom. The three of us left at the table heard the siren, and shortly thereafter, she slunk back into her seat, face flushed to the hairline.

“Did you lift the handle?” I asked, eyebrows raised.

She nodded rapidly, head tucked between her shoulders, eyes looking alarmed.

We laughed then, and dug into our pasta, which had finally arrived.

The next morning at the hotel, we all got dressed in our formal clothes. I stood watching as my husband helped my son tie his unfamiliar tie by reaching over his shoulders from behind while both looked into the mirror. I smiled at the contortions of my husband’s face, tongue tip angled toward the corner of his mouth, while he thought through how to tie a tie that wasn’t around his own neck. Then, we drove to the funeral home for the last viewing and the subsequent caravan to the church. My husband and children sat in the row at the back of the room where the casket was, and I went to the front row to sit beside my dad. More friends and relatives, including cousins I’d not seen in 30 years, filed into the room and took seats while John Denver’s song “Rocky Mountain High” played in the outer room.

Dad was holding up pretty well for his 91 years and the effort of receiving everyone who had come to the previous night’s calling hours. Around the room were displayed flower arrangements, a cherub carved from stone, and a collection of photos of my mother at various events – my parents’ wedding, cocktail parties, and a formal dinner at which my mother wore a slinky green dress, dangling crystal earrings, and a bouffant hairdo that made her look like a movie star.

While we waited for the signal from the funeral director to begin the last prayer, Dad pointed to the enormous spray of blood-red roses blanketing the closed lower half of the casket. They are stunning and highlight the polished cherry wood of the casket itself. Then Dad tolds me the story of the first bouquet of roses he bought Mom for Valentine’s Day after they were married. They didn’t have much money then and Dad couldn’t afford to buy a whole dozen, so he brought home six red roses, set them in a vase on the sideboard, and leaned a mirror against the wall behind them to make the bouquet seem larger.

I laughed at his description and asked, “Did she notice?”

He chuckled. “Yep.”

After many years of similar bouquets, given on similar occasions, she eventually told him to stop bringing her flowers as they would just die and she’d like something that stayed around awhile. Most likely she meant something shiny.

A few moments later, the funeral director ushered the priest into the room and we all stood for the final prayer before the casket was closed. When the priest finished, each of us filed past Mom, lying still on her white satin lining in her refined black knit dress. As I bent to kiss her goodbye, I noticed that along with her prayer book and rosary was tucked a recipe card. My sister had not forgotten about the flask, but decided it would be better to include the instructions for making a Manhattan instead, to be sure God got it right when Mom arrived.

Climbing into the car in the parking lot, my husband, daughter and I found ourselves third in line after the hearse, behind my father’s and brother’s cars. My son had stayed behind to carry out his task as pallbearer.

As we waited for others to get into their cars, the funeral director worked his way down the line, planting a small black flag on a magnetic base on the hood of each car. He told us to keep our headlights on.

And that’s when the questions began — not from my son or daughter, as I was expecting, but from my husband, and I realized I had wasted the time preparing my son so carefully; he seemed to be carrying out his role without concern.

To understand the origin of his questions, you need to know that my husband was born in Japan and so he was not familiar with the Catholic rituals surrounding life (and death) events. As a scientist, he is also of a curious mind (which I mean in both senses of the word). When it comes to the final ceremony in his home country, it’s all about swift cremation and enshrinement in an urn in a closely packed cemetery on a hillside. There is little pageantry, and the deceased is tucked away within a couple of days. He had never attended an American-style funeral.

“What’s the flag for?” he asked.

“That’s just to mark that we’re part of the procession,” I answered.

“Why do we have to keep the headlights on?”

“I dunno. It’s just tradition, a way to mark the solemnity of the event.”

“What happens now?” he asked as Alan joined us in the car, the casket having been loaded into the hearse.

“Well,” I began, “First we go to the church for the funeral, which should last about an hour. After that, we go out to the cemetery for a brief ceremony, and then we’ll go back to the school beside the church for lunch.”

And that’s what happened next – the slow procession of cars behind the hearse through the side streets of town to church. Alan and his cousins carried out their role as pallbearers. During the funeral Mass, the priest recited the necessary prayers and sprinkled the casket with holy water. Dad entered Mom’s name into the final record (though he had to start over because he began at first to sign his own name). My second sister and I read our assigned passages, and my first sister sang the designated final hymn.

In the car on the way to the cemetery, my husband’s questions began again.

“What’s that police car doing up front?” he asked, nodding at the cruiser preceding the line of cars moving slowly away from the church.

“It’s customary for the police to lead the procession to the cemetery,” I answered.

“Why are those cars pulling over on the other side of the road?”

“Well, that’s a traditional sign of respect – the living acknowledging the passing of the dead. It’s kind of a nice honor.“

“How come we get to run the red lights?”

“Why can’t we drive faster?”

Once again my brain was slow on the uptake, and I found myself – ever the teacher – shifting from the inkling of irritation over explaining the obvious to studiously answering his questions. Moving from annoyed wife to erudite instructor, I realized that, yes, this was actually my mother’s funeral we were talking about, and my irritation melted into amusement.

When the procession arrived at the cemetery, the police car turned off and the rest of us followed the hearse to park randomly around the gravel paths separating the rows of headstones. We got out of the car and took seats graveside, waiting for the priest to arrive. The watery blue sky reminded us that fall had arrived and we could hear the slight wind rustling the dead corn stalks in the field behind the cemetery. Maybe this was the reason Mom left in October – to avoid having to face another frigid Midwestern winter.

The casket had been set on its frame over the grave, and the area around the grave, including the chairs we were sitting in, was sheltered by an awning erected on poles.

My husband, scrutinizing the casket on its frame above the deep grave, noticed the finely polished wood, the shining brass handles.

“How much does something like that cost?” he asked.

“Um, it depends,” I said, “on what it’s made of.”

“But that’s a nice coffin,” he stated. “Do they just put it in the ground like that?”

“No, dear, they put it in a vault.”

“What’s that?”

“That big concrete box sitting in front of the first row of chairs, with the etching of a dove on the lid.”

“They put the casket in that box?”

“Yes.”

“Why?”

“Um, I don’t know. To protect it? That’s just how it’s done.”

“So they put all that in the ground?” he said in amazement, trying to figure out this strange protocol.

“Yes.”

“Will Alan have to get down in the hole to help?”

“Uh, no.”

“How do they get it down there then?”

“Um, I don’t know. The funeral director takes care of all that after we leave. I think they use a machine to lower it in.”

“So they could bring it back up?”

“Um, yeah, in theory they could, but we don’t usually do that, unless there’s been a crime and the body has to be exhumed.”

Just then, the priest stepped to the side of the grave and began his last round of prayers. When he closed his book for the last time, everyone stood up and began milling around the seats and out into the gravel pathways. Like my siblings and a few others, I stepped up to the casket and removed several roses from the flower blanket that still adorned the lower end. People came to speak to my father and shake his hand or offer a hug before they drifted off to their cars or to look for other dead relatives in other parts of the cemetery.

We stayed awhile under the awning, helping Dad greet those who came to honor her and console him. Then we moved out among the rows of headstones and, as my husband stood surveying how the cemetery was laid out (and apparently how the dead were laid out in it), the questions began again.

“So all the dead people are down in the ground?”

“Yes.”

“So we’re standing on top of dead people?”

“Um, yeah.”

“Well, if these are called headstones, shouldn’t the head of the person be under it?”

“Well, yeah, that would make sense, but the stone is usually already in place before the person dies. I think it’s good enough to make sure the head is at that end.”

“How do they know they’ve got her head at the right end?”

“Um, well, I think there’s some sort of indicator on the casket.”

To be honest, I was just guessing. I have no idea how to tell which end is up. It’s not something I’d ever thought about. But once you assume a role, it’s hard to give it up. So I concluded confidently, “The funeral director probably knows which end goes up.”

My husband’s mother had died several months before my own. Had we been able to attend her funeral in Japan, I would likely have had similar questions and would have welcomed the explanations. But I doubt my husband’s irritation would have made the same transformation as mine.

A few days later, I was back in my classroom on the west coast, where the students were asking about how much detail a writer should include in a descriptive essay.

“It depends on the knowledge base of the audience,” I replied.

And there it was – the perfect chance. “For example, here’s what happened to me over the weekend….” I began. And I told them of my husband’s questions and my answers, and found myself amused all over again.

On that night in October, Mom slipped her earthly bonds and left her slightly odd family behind. But — she left me this story to tell.

Carol was 80 years old and, for most of the past 40 years, had lived alone in the small house she’d grown up in, on a shaded street in a tiny town in Indiana.

Carol was 80 years old and, for most of the past 40 years, had lived alone in the small house she’d grown up in, on a shaded street in a tiny town in Indiana.